Recent rains in both countries have helped put out the wildfires, which were likely started by farmers and ranchers using slash-and-burn agricultural methods.

Recent rains in both countries have helped put out the wildfires, which were likely started by farmers and ranchers using slash-and-burn agricultural methods.

New peatlands research center aims to reshape conservation efforts

Indonesia “I can keep my land fertile and I’m able to work regardless of the season, but my neighbor who uses the burning method has difficulties during the rains because their land becomes a swamp,” said Akhmad (Taman) Tamanuruddin, addressing delegates at the launch of a new peatland research center in Indonesia.

Taman is a farmer in Palangka Raya, the capital of Indonesia’s province of Central Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. He rejects the traditional local practice of using fire to clear residue from the fertile peatlands before planting his crops.

Instead, he applies herbicides and lets the old vegetation die off and decompose, allowing it to become a natural fertilizer.

Traditional burning practices are under scrutiny by scientists and policymakers because peatlands are effective carbon sinks. They are made up of layers of decomposed organic material built up over thousands of years. When they burn, warming gases are released into the atmosphere exacerbating climate change. Fires often burn out of control, damaging vast areas and drying out the land, rendering it useless for farming.

In 2015, the impact of wildfires was far-reaching. Fire destroyed more than 2.6 million hectares of land — an area 4.5 times the size of the Indonesian island of Bali, according to the World Bank. The price tag for the damage was more than $16 billion, the bank said.

Indonesia has since boosted efforts to ban the use of fire to clear forested peatlands to plant oil palms, maize or rice by establishing the Peatland Restoration Agency in 2016.

Legislation banning fire use to clear land was introduced in 2009 and 2014.

Research compiled in Riau province by Indonesia’s Forestry and Environment Research, Development and Innovation Agency (FOERDIA) of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MOEF) shows that land prepared by burning vegetation before planting is more productive. They examined peatlands cultivated for oil palm, rubber, corn, rice, and other food crops.

Oil palm yield in burned peatlands was found to be almost 30 percent greater than in those that were not, producing yields of about 13.3 tons per hectare a year. In peatlands that were not burned, yield was only 9.4 tons per hectare a year. Rubber tree yields were found to decrease on average by 46 percent if the land was not burned. Corn yield disparities were even more extreme.

Burning resulted in higher soil fertility in the peatlands. It also reduced acidity, contributing to the higher yields.

Aware of the yield benefits, many farmers involved in the study disregarded prohibitive legislation and burned off their fields. Of the study participants, only 49.3 percent stopped the practice, while 45.2 percent of respondents continued and 5.5 percent said they would give up on farming as they did not see any alternative to burning.

“Some farmers are unwilling to cultivate corn without burning since the yield will drop sharply and produce only a third or a quarter,” said Murniati, a scientist with FOERDIA.

“They were afraid to use the burning techniques but they don’t have enough money to finance the no-burning techniques,” Murniati added, explaining that farmers are scared of incurring penalties for violating anti-burning laws but feel they have no choice but to face the risk.

SEEKING ALTERNATIVES

Since he got involved in sustainable agriculture, Taman has trained hundreds of farmers. He adds fertile soil, dolomite, and manure to his land and plants a variety of crops, including corn, chili, and vegetables.

Initially, the cost of farming in this manner may seem more expensive, but over the long term it saves him money, Taman said, explaining the environmental benefits.

Although burning more resistant vegetation is a less expensive and easier solution, it can strip nutrient levels in the soil and spoil the peatlands in the long run.

As farmers, we need more support for infrastructure to lower costs, Taman said.

“We at least need proper roads and bridges in our village to cut distribution expenses,” he added. “It can help us big time.”

Currently, poor infrastructure causes high costs for herbicides and harvested crops. Farmers are forced to rent cars to cover a short 250-meter distance because trucks cannot fit into narrow roadways.

Finding other livelihood options might be key for helping local communities thrive while conserving peatlands, according to Dede Rohadi and Herry Purnomo, scientists with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) currently working with MOEF and several partners.

The Haze Free Sustainable Livelihoods project led by CIFOR, MOEF and the University of Lancang in Riau aims to find alternatives for farmers who cultivate crops in the province.

“We try to empower communities so they can maximize the existing livelihood potentials in their village,” said Rohadi, who leads the project.

Some villages already cultivate honey, develop fisheries and grow food crops such as chili peppers and pineapples.

In addition to the Haze-free Sustainable Livelihood project, CIFOR is currently coordinating the Community-based Fire Prevention and Peatland Restoration project with Riau University, local government, communities, and the private sector.

The latest commitment from the governments of Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Republic of the Congo, to establish the International Tropical Peatland Center (ITPC) promise for peatland preservation efforts. ITPC is currently based at CIFOR in Bogor, near Indonesia’s capital Jakarta.

It provides valuable opportunities for cooperation in the global south to ensure policymakers, practitioners, and communities have access to trustworthy information, analyses, and the tools needed to conserve and sustainably manage tropical peatlands.

Although peatlands extend over only 3 percent of the world’s land mass, they contain as much carbon as all terrestrial biomass and twice as much as all forest biomass.

About 15 percent of known peatlands have already been destroyed or degraded.

2018/11/08, Environment | By Helena Varkkey

Transboundary haze is a form of seasonal air pollution affecting up to six Southeast Asian countries on an almost annual basis.

The first reports of this phenomenon emerged in the 1980s, and the most recent serious episode took place in 2016. The most affected countries are Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. The particulate and aerosol matter that makes up the haze originates from forest and peat fires occurring during the dry season, mostly in Indonesia. When this permeates the troposphere and travels across national borders, it is known as transboundary haze.

The countries and people within reach of this smoky shroud suffer serious health, economic, and environmental consequences during each episode. The fine particles in the haze permeate deep into the lungs, which can cause serious respiratory problems, especially among young children and the elderly, sometimes resulting in death. Ophthalmological, dermatological, and psychological issues are also commonplace.

Sick days taken and school closures (during which parents often stay home to care for their children) cause significant losses in workforce productivity. These countries’ tourism industries suffer as well, as visitors have no interest in hazy skylines. Agricultural productivity and the general state of the environment also decline as the haze blocks out the sun and slows down photosynthesis.

With the countries affected all situated within the Southeast Asian region, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was quickly looked upon to be the driver of a workable regional solution to the haze. ASEAN began to formally identify transboundary haze as part of its remit in 1985. However, despite various ASEAN agreements, initiatives, and task forces since then, the haze persists. The haze’s effect on member countries is dire, and its causes are seemingly well understood, so ASEAN’s continued inability to effectively mitigate it is puzzling.

Scholars have laid the blame for ASEAN’s “failure” to solve the haze on weak regional governance; specifically, the limitations of its model of regional engagement through consensus, non-interference, non-confrontation, sensitivity, and politeness, as well as non-legalistic procedures – the so-called “ASEAN Way.” Describing this model as a “doctrine” to be adhered to at all costs, scholars such as Vinod Aggarwal and Jonathan Chow argue that member states’ desire to eliminate the haze has been unable to compete against the stronger desire to comply with the ASEAN Way.

However, other ASEAN observers, such as Tobias Nischalke and Shaun Narine, have argued that member states do not blindly follow the ASEAN Way. Nischalke’s research uncovered many examples where the ASEAN Way was only moderately adhered to at best. This contention was the entry point of my research: has ASEAN been failing on the haze because states are duty-bound to adhere to norms that do not encourage effective regional environmental governance? Or have the states been choosingto adhere to these norms because it is in their interests to do so? If so, what are these interests, who has been shaping them, and why are they not in line with a haze-free ASEAN?

To answer these questions, I spent six months in Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia conducting semi-structured interviews with over 100 individuals with experience in haze governance, including government and ASEAN officials, journalists, plantation company representatives, non-governmental organization workers, and academics.

During these conversations, several points became clear.

Firstly, the type of fire matters. While regular forest fires are most common, they usually burn tree canopies. This produces little smoke and often results only in short-term, localized haze. Peat fires, on the other hand, can spread below the surface, reaching soil. Carbon-rich soil produces especially thick and sooty smoke when burnt, and this smoke can travel great distances. These fires are also harder to put out. Hence, a small amount of fires (on peatlands) are responsible for a large portion of transboundary haze.

Secondly, peat is not naturally fire-prone. In their natural state, peatlands are flooded year-round – fires only occur when peatlands are drained in preparation for planting. This dries out the peat and makes it flammable.

Thirdly, due to the importance of peatlands as carbon sinks, Indonesian law generally does not allow these areas to be developed. Despite this, and due to the decreasing availability of mineral soil, an increasing amount of peatlands have been opened for agriculture, especially for palm oil. A trend emerged, where the increasing severity of the haze matched the region’s palm oil boom in recent decades.

Further interviews revealed that large plantation companies, both local and from Malaysia or Singapore, have managed to obtain licenses to access peatlands to plant crops like oil palm. Some of these companies deliberately use fire as the cheapest and quickest way to clear the land for planting. Even if these companies do not deliberately burn, the act of draining these lands makes them prone to accidental fires.

I found that strong patronage networks in this sector have enabled this to happen. Patronage is defined as a situation where an individual of higher socioeconomic position (patron) uses his influence and resources to provide protection or benefits for a person of lower status (client), who reciprocates by offering support and assistance to the patron. In this case, government patrons have provided the benefit of licenses to their clients, the business elites who own or are affiliated with these plantation companies. Furthermore, clients have also enjoyed their patrons’ protection from prosecution for haze-producing fires.

These networks are at work even at the ASEAN level. When they represent Indonesia at ASEAN, the patrons are still compelled to protect their clients. An effective ASEAN haze mitigation strategy would mean that their clients would lose access to lucrative income, and risk being prosecuted. Hence, these patrons choose to use the ASEAN Way, especially the principles of non-interference and non-legalistic procedures, to block any meaningful strategies. Malaysian and Singaporean patrons follow suit, as they also act to protect their own complicit companies. I argue that these patronage networks better explain the decisions made at the ASEAN level that have led to the failure of the bloc to solve the haze problem.

Since my field research, there have been some positive developments. The government of Singapore has shown a shift in its national interests, away from protecting its clients and toward the well being of its people. After several public displays of frustration with ASEAN’s lackadaisical efforts, Singapore ultimately passed its landmark Transboundary Haze Pollution Act in 2014, which empowered its courts to prosecute any party (even non-Singaporean) found to have caused haze in Singapore.

Singapore, however, has not yet been able to use this act in court, largely due to the non-cooperation of Indonesia. While ASEAN member states still meet regularly to strategize on haze matters, the strategic use of the ASEAN Way continues to limit any meaningful progress. However, as Singapore has shown, change is not impossible. I remain hopeful that other member states will eventually follow in Singapore’s footsteps to act in the common interest of the people of the region.

Helena Varkkey is a senior lecturer in the Department of International and Strategic Studies at the University of Malaya. She received her PhD in international relations from the University of Sydney in 2012 and her first book, “The Haze Problem in Southeast Asia: Palm Oil and Patronage,” was published by Routledge based on the above research in 2016.

Read Next: INDONESIA: Palm Oil Linked to Deforestation Remains on Store Shelves

This article was originally published in AsiaGlobal Online, a Hong Kong-based source of Asian perspectives on global issues. The News Lens has been authorized to republish this article.

TNL Editor: Nick Aspinwall (@Nick1Aspinwall)

Source Link: https://international.thenewslens.com/article/107781

Acid rain was a major environmental problem in the 1970s and 1980s. The phenomenon was caused by the reaction of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide from power factories with moisture in the atmosphere to generate acid, which fell onto earth as rain, poisoning lakes and destroying forests.

The situation began to improve in 1990 when the United States government and economists introduced a cap-and-trade system for power producers, which put in place a cap on permitted emissions and enabled companies to trade leftover allowances, said Richard Sandor, chairman and chief executive officer of the American Financial Exchange, an electronic exchange for financial institutions.

Sandor, who played a key role in orchestrating the cap-and-trade scheme to tackle acid rain, was speaking at a lecture organized by the National University of Singapore in the Southeast Asian city-state.

“The idea was to put a cap on the number of emissions nationally, and then lower the cap over a period of time,” he said. There was the outcry that electricity prices would skyrocket, America’s competitiveness would be hurt, and power-producing states such as Ohio or Illinois would go bankrupt.

Instead, a decade after the first cap-and-trade programme was implemented, emissions were down to around 4 million tonnes from a high of 18 million in the 1980s.

“Electricity prices went down. The cost to the US economy was $1.2 billion, but there was an annual reduction of $123 billion in medical expenses associated with lung diseases,” said Sandor, who is also known as the “father of carbon trading” for his work on carbon markets around the world. “That does not include 37,000 lives a year saved nor the restoration of rivers.”

But could market-based solutions solve the persistent problem of transboundary air pollution in Southeast Asia, asked moderator Tommy Koh, ambassador-at-large for Singapore’s foreign ministry.

Also known as the haze, it is caused by forests fires in Indonesia as land is cleared for palm oil plantations, said Koh.

Sandor offered two pieces of advice: to create a regional solution and to put a price on pollution.

Drawing from the example of acid rain, he said that the creation of local laws to regulate emissions from coal-fired plants resulted in utility companies building taller smokestacks so that emissions would blow into another state where the regulations didn’t apply.

“We thought of sulfur dioxide as a local problem, but it was as regional as [the haze] in Southeast Asia. It requires a regional agreement because local command and control, where there are externalities involved, just doesn’t work,” Sandor said.

When told that Asean—a political bloc of 10 Southeast Asian countries—already has an agreement to combat the haze, Sandor said pricing could be another solution.

Cap-and-trade markets work because companies find that it pays to pollute. “The question is, how do people get paid not to pollute?” he said. If polluters realize they could make money from cutting emissions—by selling leftover emission quotas, in the example of acid rain—they would do it.

Sandor was optimistic about the future of blockchain-based market trading, which could also empower small producers to access bigger markets. There has been a lot of hype and speculation around cryptocurrencies, which are digital tokens whose transactions are recorded on the digital open ledger that is blockchain technology, he said.

But the underlying blockchain technology is much more impactful as it can be used to facilitate trade in clean energy, as seen in South Africa’s Sun Exchange platform WePower from Lithuania, Sandor explained.

Recalling his work in Kerala state in Southern India in 2007, Sandor said he and the Chicago Climate Exchange partnered a non-governmental organization to encourage farmers to collect manure and process it using biodigesters. The methane produced was used for household cooking, and the carbon credits produced sold on the Exchange to provide additional income.

But a key obstacle was the need to travel to these remote villages to verify the carbon offsets were indeed being made, noted Sandor.

“If we had the blockchain and remote sensing … we could’ve reached 20 million rural poor [versus 150,000] because all they would’ve needed were cell phones and remote sensors and I could’ve built a blockchain registry,” he said.

Farmers who have mobile phones can record information about their crops and sustainability certification credentials on the blockchain, and take advantage of that transparency to connect with larger, international markets, said Sandor. “This is a way for an Indian farmer with a small plot of land to—because the information is recorded—be a supplier to Walmart that could never be without this technology.”

He added: “The message is: embrace change, don’t be bothered by blockchain, it’s no different to the cellphone or CNN. It’s information.”

Source Link: https://www.eco-business.com/news/is-there-a-market-based-solution-to-southeast-asias-haze-problem/

By Gregory McCann

Published: Tuesday, 02 October 2018 16:33

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen promised on Sunday that he would fix his country’s problems with rampant deforestation by shooting those who illegally chop down timber from helicopters.

“It’s correct that we are losing our forests, many are being replaced by rubber plantations,” he said, speaking to members of the Cambodian diaspora in New York.

“I acknowledge that thieves have illegally cut down timber and I am ordering them to be shot from helicopters in the sky.”

Hun Sen made a similar promise two and a half years earlier when he announced that General Sao Sokha, newly appointed as head of a task force to stop illegal logging and timber smuggling, was authorized to fire rockets at loggers from helicopters.

That order came a year after a Global Witness report showed that Hun Sen’s own personal advisor, Try Pheap, headed an illegal logging network that saw millions of dollars of rosewood smuggled to China each year.

Not a shot has been fired from helicopters since that order and the task force did not succeed in halting the flow of luxury timber across Cambodia’s borders to Vietnam.

Hun Sen’s relatives have also long been linked with the country’s illegal timber business.

With hectares of forest falling to loggers and economic land concessions dished out by Cambodia’s ruling party, the country has one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation.

Global Witness meanwhile estimates that evictions that have resulted from logging and the government giving land to agribusinesses have displaced 830,000 people, forcing some into squatting in state forests or cutting down timber themselves.

Speaking Sunday, however, Hun Sen emphasized that it was the country’s now-defunct opposition–whose leader is in exile and whose deputy leader is just out of prison–that should be blamed for illegal logging.

“In many cases [the thieves] went to cut down millions of hectares to cultivate farmlands, including groups [affiliated] with the former opposition,” he said.

Source Link: https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/8677-cambodian-pm-vows-to-shoot-loggers-from-helicopters-again

by Randal OToole 09/27/2018

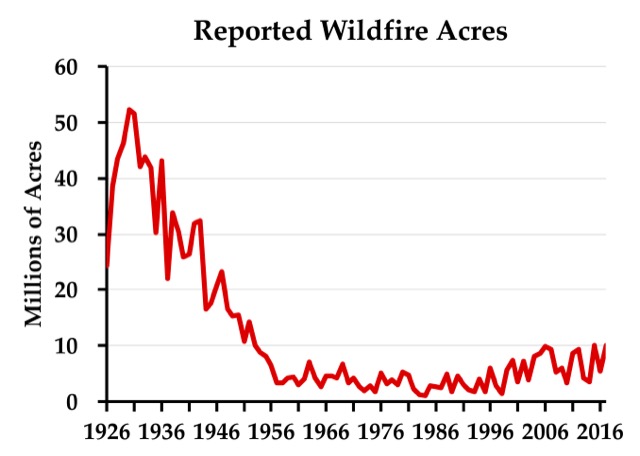

The latest wildfire situation report indicates that about 7.3 million acres have burned to date this year. That’s about 1.2 million acres less than this same date last year, but about 1.5 million acres more than the ten-year average and a lot more than the average in the 1950s and 1960s, which was about 3.9 million acres a year. Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.

Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.

While some blame the increase in acres burned on human-caused climate change, skeptics of anthropogenic warming have pointed out that, according to the official records, far more acres burned in the 1930s — close to 40 million acres a year — than in any recent decade. The 1930s were indeed a decade of unusually bad droughts that can’t be blamed on anthropogenic climate change.

While the Antiplanner isn’t persuaded that recent fires are evidence of human-caused global warming, reports of acres burned from before about 1955 are not evidence of the opposite for a simple reason: the Forest Service lied. While the Antiplanner has alluded to this before, it’s important to tell the full story so that skeptics of climate change don’t reduce their credibility by using erroneous data.

The story begins in 1908, when Congress passed the Forest Fires Emergency Funds Act, authorizing the Forest Service to use whatever funds were available from any part of its budget to put out wildfires, with the promise that Congress would reimburse those funds. As far as I know, this is the only time any democratically elected government has given a blank check to any government agency; even in wartime, the Defense Department has to live within a budget set by Congress.

This law was tested just two years later with the Big Burn of 1910, which killed 87 people as it burned 3 million acres in the northern Rocky Mountains. Congress reimbursed the funds the Forest Service spent trying (with little success) to put out the fires, but — more important — a whole generation of Forest Service leaders learned from this fire that all forest fires were bad.

In 1924, Congress passed the Clarke-McNary Act, which allowed the Forest Service with (i.e., provide funds to) “appropriate officials of the various states or other suitable agencies” in developing “systems of forest fire prevention and suppression.” The Forest Service used its financial muscle to encourage states to form fire protection districts.

This led to a conflict over the science of fire that is well documented in a 1962 book titled Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. Owners of southern pine forests believed that they needed to burn the underbrush in their forests every few years or the brush would build up, creating the fuels for uncontrollable wildfires. But the mulish Forest Service insisted that all fires were bad, so it refused to fund fire protection districts in any state that allowed prescribed burning.

The Forest Service’s stubborn attitude may have come about because most national forests were in the West, where fuel build-up was slower and in many forests didn’t lead to serious wildfire problems. But it was also a public relations problem: after convincing Congress that fire was so threatening that it deserved a blank check, the Forest Service didn’t want to dilute the message by setting fires itself.

When a state refused to ban prescribed fire, the Forest Service responded by counting all fires in that state, prescribed or wild, as wildfires. Many southern landowners believed they needed to burn their forests every four or five years, so perhaps 20 percent of forests would be burned each year, compared with less than 1 percent of forests burned through actual wildfires. Thus, counting the prescribed fires greatly inflated the total number of acres burned.

The Forest Service reluctantly and with little publicity began to reverse its anti-prescribed-fire policy in the late 1930s. After the war, the agency publicly agreed to provide fire funding to states that allowed prescribed burning. As southern states joined the cooperative program one by one, the Forest Service stopped counting prescribed burns in those states as wildfires. This explains the steady decline in acres burned from about 1946 to 1956.

There were some big fires in the West in the 1930s that were not prescribed fires. I’m pretty sure that if someone made a chart like the one shown above for just the eleven contiguous western states, it would still show a lot more acres burned in real wildfires in the 1930s than any decade since — though not by as big a margin as when southern prescribed fires are counted. The above chart should not be used to show that fires were worse in the 1930s than today, however, because it is based on a lie derived from the Forest Service’s long refusal to accept the science behind prescribed burning.

This piece first appeared on The Antiplanner.

Randal O’Toole (rot@ti.org) is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute and author of the new book, Romance of the Rails: Why the Passenger Trains We Love Are Not the Transportation We Need, which will be released by the Cato Institute on October 10.

Source Link: http://www.newgeography.com/content/006096-the-sordid-history-forest-service-fire-data

Tuesday, 25 September 2018 | 13:06 WIB

TEMPO.CO, Pekanbaru – Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) detected 12 hotspots in Riau Province, which became an early indication of forest and land fire, on Tuesday morning.

Based on the data from BMKG Pekanbaru Station that was updated at 7:00 am, Riau still dominates the number of hotspots on Sumatra Island since the beginning of this week. In total, there are 23 hotspots in Sumatra, and 12 of them are in Riau.

There are five hotspots in South Sumatra, three in Lampung, two in Bangka Belitung, and one in Bengkulu.

Head of BMKG Pekanbaru Station, Sukisno stated the number of hotspots increased compared to on Monday afternoon, September 24, which was 11 hotspots. Of the 12 hotspots, the most were in Pelalawan District, five hotspots.

In Siak and Meranti Islands, there were three hotspots and Indragiri Hulu has one hotspot. In addition, there were two hotspots that have a level of confidence above 70 percent. “These two hotspots are in Pelalawan and Meranti Islands,” he said.

ANTARA

Source Link: http://en.tempo.co/read/news/2018/09/25/206921950/BMKG-Detects-12-Hotspots-in-Riau-Indication-of-Forest-Fire

The finding is “a really big deal,” says tropical ecologist Daniel Nepstad, director of the Earth Innovation Institute, an environmental nonprofit in San Francisco, California, because it suggests that corporate commitments alone are not going to adequately protect forests from expanding agriculture.

Researchers already had a detailed global picture of forest loss and regrowth. In 2013, a team led by Matthew Hansen, a remote-sensing expert at the University of Maryland in College Park, published high-resolution maps of forest change between 2000 and 2012 from satellite imagery. But the maps, available online, didn’t reveal where deforestation—the permanent loss of forest—was taking place.